Back to Goin' Down South

The blues, a cultural product native to the United States, was initially produced by a people who have historically been excluded from the conventional American institutional and cultural life. Musical historians cannot pinpoint the exact time or location where the blues began, but they have enough belief to suggest that blues origins predate slavery, possibly (in its most basic level) originating in Africa. Their evidence spawns from the array of musical forms sung and played by the black people working the fields of southern America.

| Plainsong chants were the norm in the savannah region of West Africa. There was a lesser influence of drums in these African grasslands and a greater abundance of string instruments. The people of this region were brought to America against there will as slaves. They were forced to leave their families, culture, homes, identity, everything behind, everything except for their strong willed hearts and minds. Nothing could prevent their musical heritage from emerging, and over time it has evolved into the vocal and instrumental presentation of the blues. |  |

While laboring on plantations and expansive farmlands, topography not too unlike their familiar grasslands, the slaves began their habitual call-and-response field hollers, work songs, and chants. The words and musical tone represented their feelings. When instruments were added, they would bend the strings to find off-pitch tones that perfectly expressed their weariness. Bent and flattened notes are standard features within the blues structure. In fact, there are many similarities between these field songs and modern day blues in the significance of improvisational verse, wails and vocal leaps, the mixture of wit and melancholy, and the sliding notes.

"when I lay my burden down" |

The white society tried to strip the black heritage simply because they believed the music contained coded messages signaling a revolt. In the end, the more musically talented slaves were trained by their white owners to play more European styles for entertainment purposes and parties thus beginning a co-existence of the two cultures however unconventional. The black people adopted the basic chord structure and restricted their melody to a three chord configuration of the diatonic scale. There would be many innovations in the decades following (polyrhythm, flatted thirds/sevenths, minor chords, bottleneck fretting) that would eventually lead the way to blues, jazz, and rock. |

One area that was somewhat an exception to the wide practice of racial “etiquette” was in the hills of Tennessee and Mississippi, home to a number of farmers who were too poor to afford fancy balls and dances and home to a heavier white population, but still radically divided. And yet, in a way, the whites and blacks tending the land had more commonality than their wealthy neighbors. Poverty could also be the reason for the slower evolution of music in this state. Northern Mississippi and the hills of Tennessee kept a musical form that was lost in other parts of the south. Crude, handmade instruments were constructed keeping the music constrained to only a few notes or chords. The harmonic expansion was limited on these instruments making the music repetitive. As a result, they were playing the same notes, but experimenting with rhythm. The music evolved into strongly rhythmic pieces in which the melodies were mostly reduced to simple reiterative phrases, or in other words, trance-like. This region was creating a sub-genre of the blues later to be known as Hill Country Blues.

|

Once the south entered the post-civil war era more whites and blacks alike were trapped by the cruel tenant-farming system and experiencing poor social and economic conditions. The musical tradition naturally reacted off of this backlash. Music was a narrative of poverty, lower social status, unstable relationships, and addictions. Natural disasters added tones of survival, starvation, and despair. This era led to interplay between African and European musical forms. |

More specifically, the hill country strain which even has similarities with north Georgia, Alabama, Carolina, and Virginia has a musical sound similar to the Scotch-Irish/European tradition, but displayed the same life themes coming from the aftermath of war. The north Mississippi sound is characterized by a repeated use of one particular chordal run. There are only one to three chords in its progression on top of a driving beat. While the southern regions developed what is known as the 12-bar blues pattern, the hill country stays with an elongated bar line rarely changing its modal form. It becomes a hypnotic drone to symbolize its feeling. Guitar players standardized what is called “open tuning,” meaning all the strings are tuned to notes within a major chord, and the chord could be played when all strings are strummed open with no finger-fretting on the left hand. This allowed more use of the slide which evolved from a literal “bottlenecking” of the guitar.

The purest example of a one chord line over a constant beat is the fife and drum band of the south. While the Irish influenced northern America with the famous fife corps of the colonial militias, an African tradition again emerged in the south. A fife was carved from a bamboo cane and holes were burned into the wood to create the different tones. The reed line was in one key that played over the drum groove of the Hill Country.

|

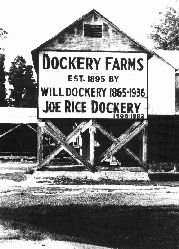

The blues as a single genre was more defined in the early 20th century. A group known today as the Pre-War (world wars) Blues musicians became the masters or architects of the style. Musicians Robert Johnson, Bukka White, Charlie Patton, Son House, Furry Lewis and Muddy Waters made the guitar the main instrument and the first recordings were made. As soon as there was modernization in transportation, the blues spread all over America in a short span of time. Many black musicians desperately wanted to get away from the Jim Crow laws of segregation, sharecropping, and constant lynching parties in the south. Recognition of their contributions did not blossom until later, and at the time a “hill country” style was not defined except what Mississippi Fred McDowell called “old country style blues.” |

The driving beat behind the Hill Country blues was refined over a few decades span by a bothersome, mutinous assemblage of musicians. Junior Kimbrough, R.L. Burnside, T-Model Ford, and several others played the blues alongside their tumultuous lives. The slow guitar solo over the heavy beat was more prominent during their time as well as the introduction of amplification and electric guitars (Kimbrough even added a bass). Otha Turner, the last great fife and drum master was recorded in the 1960s by Alan Lomax demonstrating the fife line as the solo guitar, but the best known recordings of these contemporary legends came from a man named Mathew Johnson who in the early 90s created the record label Fat Possum. The region was beginning to shine in the public eye and cleared a path for the younger generation.

The next few generations of southern blues artists had more influences to draw upon with the advances of musical recordings and the accessibility of music in general. Bands like the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin were known for drawing upon the blues structure, and eastern Indian sounds were mixing their way into blues-rock beginning with the Beatles. The bent notes of the sitar and the drone of the tambura were appealing to the psychedelic rock era. The psychedelic drone was a representation of “mind expansion” and their numb, usually drug-induced feelings. It is not surprising the young blues-rock artists today emanate and idolize rockers like Jimi Hendrix who also was known for a solo guitar over a drum groove. These young artists are mixing the styles together as well as developing new, innovative musical techniques and effects.

| A cross-fertilization of thematic content and structure from different cultures leads us to where we are today, a mixture of country, New Orleans boogie, bluegrass, jazz, rock, heavy metal, African, European, and Asian among many others. As music is categorized into sub-genres and world styles, the deeply felt personal expression of the artist still exists. The performance is what keeps the music alive after so many years of evolution and regardless of technical advances and the blues structure will remain as the foundation. America has learned a great deal from its segregated past, and a “conglomerate of cultures” is now how we define our culture; it is what we use to signify our individuality from the rest of the world. Music, and more specifically the blues, will continue to develop in unimaginable ways, but nevertheless it will always portray the human experience. |  |